|

| LUCAS OLENIUK /

TORONTO STAR |

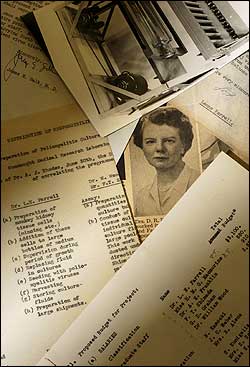

| Documents from

the Sanofi Pasteur archives help piece together the role of Dr. Leone

Farrell in finding the polio cure. From the top: a memo from Jonas

Salk; a photo of the bottles and rocking machine Farrell used to

produce mass quantities of the virus; an outline of the

responsibilities of the members of the Connaught team; and a copy of

the polio project budget from Connaught labs. |

|

Toronto's unknown polio soldier

A heroine in an unmarked grave

RITA DALY

TORONTO

STAR

In the 50 years since the world first rejoiced in the

success of Jonas Salk's polio vaccine, the name and famed

accomplishments of the renowned American researcher have grown

legendary.

Few, on the other hand, know who Leone Farrell is.

Yet there she was, tucked away in a small Toronto laboratory, a quiet,

50-year-old chemist, who, to Salk's utter delight, figured out how to

produce the virus in the vast quantities he needed for the field trial

of his vaccine.

It became the biggest medical experiment of all time, involving close

to two million children, and Farrell was among the teams of American

and Canadian scientists who waited in breathless anticipation for the

results to be announced on April 12, 1955. That triumphant day, Salk's

life changed forever.

But although Farrell's contribution was recognized by her

contemporaries, she returned to work in relative obscurity. She

continued to publish research papers well into her 60s and lived to the

age of 82. But she died alone. Her gravesite in the Park Lawn Cemetery

just west of High Park reveals nothing of the key role she played in

eradicating polio. Her remains are buried in Lot 707, in an unmarked

grave.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, polio swept North

America in epidemic waves, crippling and killing tens of thousands of

children. The poliomyelitis virus entered the body through the mouth,

invaded the bloodstream and could be carried to the central nervous

system, causing paralysis and, in some cases, death.

Epidemics struck in 1931 and again in 1937. In Toronto, children were

kept indoors, swimming pools, parks and churches were closed and the

start of school delayed.

Stricken families were quarantined. Another epidemic hit in 1946. The

worst in the U.S. came in 1952; Canada's worst year was 1953, when

9,000 children were infected.

News reports appeared daily on the horrors of school-aged children

suddenly unable to walk. Others died days after contracting the virus.

Originally thought to be a children's disease, polio also struck

parents, nurses and teachers; many became permanently imprisoned in

iron lungs.

During the 1930s and 1940s, polio researchers throughout the world were

on the hunt for a cure. Small breakthroughs were achieved in

understanding the virus, but they were often countered by frustrating

setbacks, cost being one.

In 1949, Harvard researchers discovered a way to grow the poliovirus in

a test tube. Suddenly, the scientific community was in a race to create

a vaccine.

Salk made his discovery in 1952, as the worst epidemic yet gripped the

United States. While conducting tests in his University of Pittsburgh

laboratory, the bespectacled scientist came up with an experimental

vaccine containing "killed," or inactivated virus, which could trigger

a person's blood to build immunity. His team proved it worked with

months and months of tests in monkeys, and later in a small group of

volunteers.

Salk now faced another challenge: how to mass-produce the polio virus

in order to treat the millions clamouring for it.

North of the border, Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, owned by

the University of Toronto, had been conducting its own polio research

since the late 1930s. Research was briefly interrupted by the Second

World War but resumed before the war ended. According to Canadian

medical historian Christopher Rutty, Connaught's reputation as a true

academic research centre put scientists like Leone Farrell in a unique

position to play a major role in what unfolded over the coming decade.

Unlike the pharmaceutical companies to the south, Connaught's interest

lay squarely in scientific research, vaccine production and public

health teaching.

"It didn't have to answer to shareholders, it didn't have that

corporate thinking and it didn't have competitors. It was really the

only one of its kind in Canada," says Rutty, whose doctoral thesis on

polio will soon be published in a book titled The Middle Class

Plague.

`What greater

accolade can you

get than knowing

you helped save

thousands of kids

from becoming paralyzed'

|

For that reason, the U.S. National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis,

or March of Dimes — founded by then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt,

himself crippled by the disease — had been quietly pouring money into

Connaught's polio research. By the late 1940s, the company had set up

its own special polio team led by British virologist Dr. Andrew J.

Rhodes.

Farrell was asked to join the team in 1952 — the year that Salk made

his crucial discovery.

Born in Monkland, a rural community south of Ottawa, Farrell was raised

in Toronto. "Very much a lady" is how one of Farrell's colleagues

described her, recalling that she always wore suits and heels and kept

her hair short and neat.

Leone Norwood Farrell was no ordinary lady, however. She had, by age

29, obtained a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Toronto. It was

a rare feat for women in those days; a mere handful of Canadian women

each year obtained PhDs in the 1930s.

Farrell joined the staff at Connaught in 1934, 20 years before the

polio field trials. Her specialty was the study of fungi, and she had

spent two years working as a chemist looking at yeasts in honey for the

National Research Council of Canada. She was hired by Connaught to do

studies on staphylococcus toxoids and conducted significant studies on

antibiotics, penicillin and the prevention of bacterial infections such

as diphtheria, cholera and whooping cough.

Farrell lived alone on the second floor of a two-bedroom balcony

apartment on the corner of Avenue Rd. and Oriole Parkway and each day

traveled the six kilometres south to her laboratory at the U of T

campus. Not much more is known of her personal life; her colleagues

remember her dedication and skill but remember little about her

interests, her habits, her passions.

In 1943, Connaught — by then a world leader in the development and

manufacture of vaccines, insulin and penicillin — purchased Knox

College and moved its research and production operations to the

towering Gothic revival building on Spadina Crescent.

It was during this period that Farrell came up with a unique method of

gently "rocking" large bottles containing the pertussis bacteria to

stimulate its growth for production of a whooping cough vaccine. This

discovery would prove to be crucial 10 years later in the race against

polio.

Connaught's first major polio breakthrough came in 1951. Earlier, its

cancer researchers had developed the first synthetic medium, Medium

199. Other Connaught scientists tried the medium for growing the polio

virus on monkey kidney tissue and found that the virus rapidly

multiplied in the chemically pure fluid. Suddenly, it was Farrell's job

to find a way to produce the virus in bulk quantities.

The production race was on.

"Leone was probably the most experienced person in that atmosphere. Her

specialty had been the mass production of bacterial cultures," said

79-year-old Frank Shimada, a researcher who was part of the testing

process and, in his mid-20s at the time, the youngest member of the

polio project.

In the course of regular meetings held at the Spadina lab in 1952,

Farrell, Shimada and others discussed how to grow the virus, what

containers to use, how much medium to use. It was constant trial and

error. Farrell was "a good person and a team player," he recalled. "She

knew what she was doing. She was a classic researcher and disciplined

in her work to the extent that she knew you laid out a plan and

followed it carefully for things to get done."

It took months, but research would finally prove the rocking-bottle

method used in Farrell's pertussis studies, later to be called the

"Toronto technique," was the solution they'd been looking for.

Using large, rectangular 5-litre bottles, Farrell adhered a tiny piece

of monkey kidney tissue cells to the inside glass, added the medium

and, over the course of several days, gently rocked the bottles on

specially built machines to agitate the fluid and spur cell production.

The bottles were kept in incubator rooms warmed to a body temperature

of 37C. A few degrees higher and the entire batch could be destroyed.

The polio virus was then added to infect the cells and the rocking

continued for several more days. The gratifying result was an abundance

of live polio virus.

With a mass vaccine now in sight, Connaught in 1953 was handed the

prestigious and painstaking task of supplying almost all of the 3,000

litres of virus fluids needed for Salk's field trials. Farrell remained

in charge of what now became a vast and intricate production involving

many more monkeys, medium and bottles, more buildings and more staff to

train. During this period, at least 165 monkeys a week were required to

produce the virus, Rutty said.

"This all had to be done from the ground up," recalled Shimada. "They

had to build labs, incubators, the whole bit. Techniques had to be

developed right down to special washing instructions to clean the

bottles."

Leone Farrell

has been

pretty much written

out of history

|

Farrell was instrumental in the design and implementation of it all —

an achievement recognized in the dry, bureaucratic language of an

unsigned career summary placed in her employment file.

"The breadth of these accomplishments bears testimony to the knowledge

and mental fertility enjoyed by Dr. Farrell. Never was she lacking in

basic ideas of how to accomplish her scientific goals," reads the

summary, which is now part of the Connaught archival collection.

"She was a very serious person. She was always doing research. It was

always `try this, try that,'" recalls former colleague Stephanie

Schenk. Schenk, now retired, joined Connaught as a young research

assistant in early 1954, by which time Farrell and others were already

working round-the-clock to produce large volumes of the live virus.

"I didn't know Dr. Farrell all that well, but back then everyone was so

wrapped up in their work. They were so dedicated, it was unbelievable."

In the crucial months leading up to the field trials, bottles of the

live virus were packed in ice, then placed inside dairy cans and loaded

onto a station wagon at the rear doors of the Spadina building. From

there the precious cargo was raced twice weekly to the U.S., crossing

the border at Detroit on its way to two American drug firms where the

virus was "killed," or inactivated, for Salk's use.

Salk, in a signed letter to Connaught director Robert Defries shortly

before the trial results were announced in 1955, thanked the Connaught

team for their "Herculean task" in providing the virus. When the

momentous day arrived — April 12, 1955 — hundreds of scientists

gathered in Ann Arbor, Mich., where the results were being announced.

In Toronto, nearly 700 doctors, technicians and nurses crowded into the

Crystal Ballroom at the King Edward Hotel to watch the report on two

dozen TV sets installed specifically for the event.

The late-edition headlines that day said it all — the Salk polio

vaccine had proven safe and 80 to 90 per cent effective in tests on

children across the United States and parts of Canada and Finland. With

the news, mass immunizations for millions of Canadian and American

schoolchildren and their parents immediately got under way.

In the days following the announcement, Canadian journalists rushed to

the Toronto lab for interviews and photographs. The faces of the

Connaught team, including Farrell's, were splashed across the front

page of the Globe and Mail. A proud Defries took his team out

for dinner at the Royal York Hotel.

"I was totally lost in the limelight," recalled Shimada. "That was the

moment when you thought, `My God, we're making history.' Until then

there wasn't any of that, because that wasn't our purpose."

In the months and years since, some Canadian politicians have felt

Connaught — later swallowed up by pharmaceutical giant Sanofi Pasteur —

did not get the recognition from Americans that it deserved. Rutty

argues, however, that Salk was in an impossible situation because so

many people had been involved in helping tie all the pieces together,

including researchers in his own lab who also felt slighted. Salk, for

instance, appeared alone on the cover of Time magazine in 1954.

Even so, Farrell has pretty much been written out of history.

University of Victoria women's studies professor Marianne Gosztonyi

Ainley, whose book Essays on Canadian Women and Science

reflects on the historical record of women scientists, hadn't heard of

Farrell or her accomplishments. Her case, Ainley said, raises a lot of

questions not just about who she was but about who gets credit for

scientific discoveries and whose name gets perpetuated.

"The public often has trouble understanding that scientific discoveries

are team efforts," she said. "Farrell should be remembered. Her

accomplishments should be remembered."

Last week, a commemorative piece on Salk published in the Journal

of the American Medical Association recounted the contributions of

scientists, including Salk, to "one of the greatest achievements of the

20th century." Once again, there is no mention of the role played by

Connaught, by Farrell, or anyone, for that matter, who was part of the

polio effort in Toronto — names like Defries, Rhodes, Shimada, Taylor,

Macmorine, Wood, Graham, Franklin, Morgan, Parker or Morton.

Shimada says that if Farrell were alive today, it's doubtful she would

care.

"When you're in medicine, what greater accolade can you get than

knowing you helped save thousands of kids from becoming paralyzed? The

important thing is that people know in their own hearts they are

contributors. That's what it's all about."

The former Connaught laboratories building on Spadina Crescent is

slated to undergo a major renovation to house fine arts. The

high-ceilinged hallway on the second floor where Farrell worked is now

quiet. The labs are gone; a few classrooms and offices are in their

place.

The only evidence of those exciting days are three heavy wooden doors,

behind which the live virus was kept cold prior to transport.

They remain bolted shut.

› Great

subscription deals here!

|