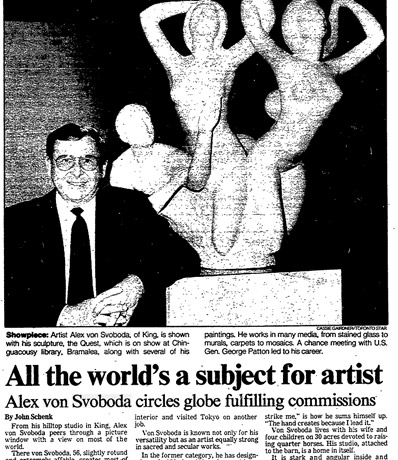

& THE RE-DISCOVERY OF A MASTER ARTIST

ALEXANDER VON SVOBODA

Visit Alexander von Svoboda's website

HHRS Home | Story of the Connaught Laboratories Mosaic | Sampling of Alex's Works | List of Works

(Above/ below) Mosaic shortly after its completion in 1966 over main entrance of Gooderham Building (#83) at Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, Dufferin Division, University of Toronto. (click images for larger views) |

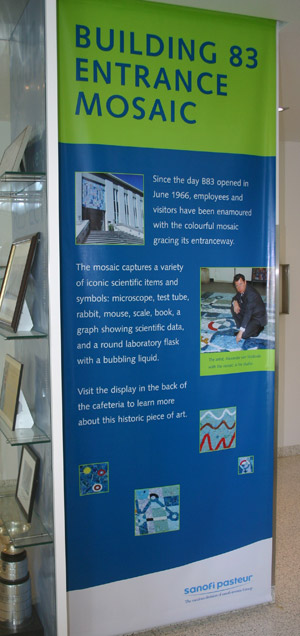

Alexander von Svoboda inspecting the mosaic in his studio before it was installed in 1966. (Right) Display posters in July 2008 located in the main lobby of Building 83 (top), and in the Cafeteria (below) at Sanofi Pasteur's Connaught Campus celebrating the Mosaic. |

|

(Above/ below) Mosaic in July 2008 at what is now known as Sanofi Pasteur Limited (Connaught Campus), 1755 Steeles Ave. West, Toronto. The mosaic is about to have a few of its tiles repaired to restore it to its original condition. |

The mosaic was used on the cover of the Connaught Medical Research Laboratories' Annual Reports from 1966-67 through 1972-73. |

(Right) Alex today in his Barrie, Ontario, studio, where he remains a prolific artist, especially painting local landscapes, and also traveling widely to paint seascapes, wildlife and Native Americans. |

Unraveling the Mystery of the Connaught Mural:

Alexander von Svoboda and the Building 83 Mosaic

By Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D.

One of the most distinctive features of sanofi pasteur’s Connaught Campus in Toronto is a large mosaic mural displayed above the front entrance of the main administrative building of the site, known as Building 83. Many employees and visitors have wondered about the story behind this beautiful work of art. What does it mean? How was it produced? Who was the artist who created it?

Building 83, along with #81 and #82, were officially opened on June 21, 1966, and, as Connaught’s Annual Report for 1965-66 noted, “were designed as a group and display a degree of beauty and dignity worthy of the men they commemorate:” Dr. John G. FitzGerald (#81), the founder of Connaught Laboratories; Dr. Donald T. Fraser (#82), pioneer of vaccine research and development; and Albert E. Gooderham (#83), who donated the land upon which the company has grown. In addition to the design of the buildings themselves, it was decided to add a further distinction by commissioning a unique work of art to adorn the front entrance of the Gooderham Building that would symbolize the mission of the Laboratories.

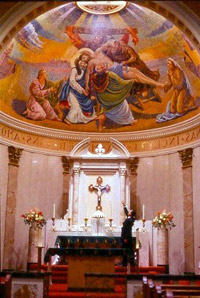

In the mid-1960s, one of the most prominent artists in Canada, and indeed the world, specializing in the type of building artwork Connaught’s leaders were looking for, was Alexander von Svoboda. Born in Vienna in 1929, von Svoboda arrived in Toronto in 1950 with but $10 in his pocket and an inexorable drive to be an artist on a large scale. At age 15, following a childhood of wealth, privilege and art school, von Svoboda endured service in the Nazi army during WWII for suicide missions. He was then captured by the Russian army for service in Siberia and soon engineered an escape that led to an arduous 6,000-mile trek back to Austria. He then befriended a group of American soldiers, which lead to service as General George Patton’s interpreter, and finally a position in the U.S. Army as an artist and designer of hospitals and chapels across Europe. Further art studies, and a realization that Europe was too small for his ambitions, prompted von Svoboda’s move to Canada, although his first years in Toronto were spent doing more general labour than artistic jobs. While his first projects included creating distinctive designs and artwork for restaurants, hotels and private residences, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, von Svoboda focused most of his considerable talents undertaking increasingly complex liturgical works for churches and synagogues. Most of von Svoboda’s creations involved large mosaic murals produced using a glass tile material known as “Smalti,” and a classical mosaic creation technique developed in Italy, which Svoboda mastered and brought to North America.

The 20 x 20 foot mosaic von Svoboda created for Connaught used hand-cut placed Smalti, which is a type of molten glass that comes out of a furnace as a thin pancake and processed and coloured using a secret method passed on from generation to generation. The pancake is cut to the required shape using a sharp hammer and glued onto the paper design in reverse. The wall is coated in cement and each one square foot section of paper with the mosaic glued on is pressed into the fresh cement and the paper is slowly removed with water. The Connaught mosaic took a total of 341 hours to complete, or over 42 days, involving a team of skilled mosaic technicians, including 5 skilled tile setters, who, as von Svoboda noted, installed the artwork “the same way as the artists installed mosaic thousands of years ago in Europe.”

The design of the mural, in von Svoboda’s words, symbolizes “the progress and research of the Connaught Labs company, and will outlive the next century.” It captures a variety of iconic scientific items and symbols, including a microscope that spans most of the right side of the design, while a test tube dominates the left side. Other images are integrated into the collage, including a rabbit and mouse, which serve important roles as test animals, a scale, an open book, a graph showing scientific data, and a round laboratory flask with a bubbling liquid. There are several other symbols in the design, including the iconic symbols for male (centre right) and female (centre), the world (lower centre left), positive and negative electric charges (top right of centre).

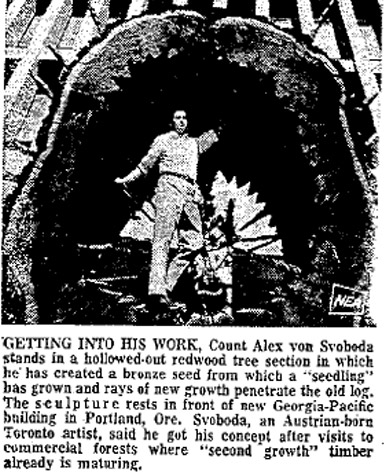

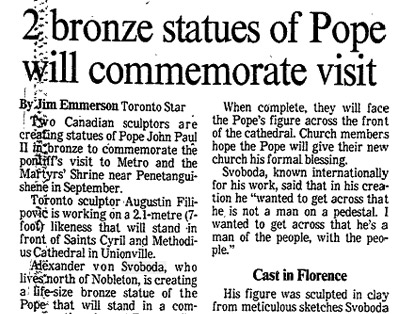

During the 20 years following the completion of the Connaught mural, the pace and scale of Alexander von Svoboda’s creations increased remarkably, including a wide variety of commercial, residential and liturgical projects in the Toronto area, across Canada and in many parts of the world. Among his most impressive works include perhaps the largest sculpture ever created in the modern era, entitled “Quest,” which featured several figures in a fountain carved from a 200-ton block of pure marble, “Perpetuity,” which is a giant cross section of a redwood tree hollowed out, petrified and embellished with a bronzed sapling tree placed inside, and a life-size bronze statue of Pope John Paul II for his 1984 visit to Toronto. By the time von Svoboda retired in the late 1980s, the type of large artworks he specialized in, particularly mosaics murals based on classical methods, essentially retired with him. Such projects simply became too complex and expensive for anyone to undertake. However, the ever restless artist did not stop working and since his retirement has maintained an remarkable pace, focused mainly on drawing and painting a wide variety of subjects near his Barrie, Ontario, home, and in many places around the world, and using his computer to document and catalogue his incredible collection of work.Below is a small sampling of Alex's enormous body of work, highlighting his large public art, hospital projects (donor wall and mosaic murals), fountains, church mosaics and sculptures, and some of his recent paintings.

All artwork Copyright 2008 by Alexander von Svoboda